Introduction

The landscape of healthcare for individuals eligible for both Medicare and Medicaid, often referred to as dual eligible beneficiaries, is complex and frequently fragmented. Recognizing this challenge, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) initiated a program to foster integrated care models. In April 2011, Massachusetts was among the first states awarded a design contract to develop and implement a service delivery and payment model aimed at integrating care for this vulnerable population. This initiative paved the way for the Masshealth One Care Program, a demonstration project designed to streamline healthcare access, improve care coordination, and align financing for dual eligible beneficiaries in Massachusetts. This program, known as One Care, represents a significant step towards a more cohesive and efficient healthcare system for individuals with complex needs. The MassHealth One Care program seeks to address the historical disconnect between Medicare and Medicaid services, offering a more unified approach to care.

Background of Integrated Care Demonstrations

State Integrated Care and Financial Alignment Demonstrations for Dual Eligible Beneficiaries are collaborative ventures between states and CMS. Their primary goal is to create more integrated systems for financing and delivering healthcare to over 10 million individuals nationwide who qualify for both Medicare and Medicaid. These beneficiaries, often facing significant health challenges and economic hardship, require a system that is both responsive and coordinated. Born out of the Affordable Care Act, these demonstrations are testing innovative models – primarily capitated and managed Fee-For-Service (FFS) arrangements – to better synchronize Medicare and Medicaid benefits and funding. The ultimate objectives are to enhance care coordination, improve the quality of healthcare services, and achieve cost efficiencies within the system. The MassHealth One Care program is a key example of these efforts, focusing on a capitated financial model.

Massachusetts solidified its commitment to this integrated approach by finalizing a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with CMS in August 2012, marking it as the pioneering state to test a capitated financial alignment model. Subsequently, in October 2013, Massachusetts launched One Care, a 3-year capitated demonstration program. The initial launch faced several postponements from the originally planned January and April 2013 dates, eventually settling on October 2013. These delays underscored the intricate planning and coordination required to enact substantial changes in financial and service delivery systems, particularly for beneficiaries with intricate health needs. However, this additional time proved valuable, allowing stakeholders to engage in extensive discussions and address concerns, ultimately strengthening the program’s design. The demonstration was initially scheduled to operate until December 2016.

Initially envisioned as a statewide program, the MassHealth One Care program commenced in October 2013 across nine of Massachusetts’ fourteen counties. This initial phase encompassed approximately 96,449 of the state’s estimated 110,000 dual eligible beneficiaries aged 21-64. A distinctive aspect of the Massachusetts demonstration, in comparison to similar initiatives in other states, is its specific focus on the non-elderly dual eligible population. Furthermore, it mandates that participating health plans contract with Independent Living Long-Term Services and Supports (LTSS) coordinators from community-based organizations, ensuring beneficiaries have access to independent support and advocacy. This report delves into the early implementation of the MassHealth One Care program, offering insights that can be valuable for other states embarking on similar demonstrations. These early findings are particularly pertinent as formal evaluation reports from CMS were not anticipated until 2016.

Research Approach to Understand One Care Implementation

To gain a comprehensive understanding of the MassHealth One Care program‘s early stages, a qualitative research approach was employed. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with a diverse group of leaders actively involved in the design and initial implementation of One Care. These interviews spanned a nine-month period, from February to November 2014, commencing five months post-program launch to allow interviewees to develop practical experience with One Care.

A semi-structured interview guide was developed to ensure consistency while allowing for in-depth exploration of specific perspectives. It included general questions for all participants and targeted inquiries tailored to the unique roles of different interviewee categories. A total of 37 stakeholders were interviewed, representing a broad spectrum of perspectives within the MassHealth One Care program. These included representatives from various state government agencies involved in health and social services for dual eligible individuals, medical, behavioral health, and social service provider organizations, consumer advocacy groups, and participating health plans.

Interviews were conducted by teams of two to four authors of the report, facilitating observation comparison and enhancing the reliability of the documented early implementation experiences. In several instances, participants were interviewed multiple times over the study period to track the evolution of perceptions regarding One Care’s implementation. Data analysis followed an iterative process to identify recurring themes and critical insights. Furthermore, publicly available documents related to the planning and implementation phases of MassHealth One Care program were reviewed to provide context and corroboration.

Planning and Launch of the One Care Demonstration

Massachusetts’ proactive engagement in the dual eligible demonstration aligns with its history of healthcare reform innovation. Several key factors motivated the development of an integrated care model specifically for dual eligible beneficiaries under 65 in the state. Massachusetts had already transitioned most of its MassHealth (the state Medicaid program) beneficiaries under 65 into managed care frameworks, with specific exceptions. However, dual eligible beneficiaries largely remained within an uncoordinated, fee-for-service (FFS) system. Drawing on its positive experience with care coordination through the Senior Care Options (SCO) program for seniors, Massachusetts sought to extend similar benefits to its younger beneficiaries with disabilities. Crucially, former Governor Deval Patrick, a staunch advocate for the Affordable Care Act (ACA), prioritized the dual eligible demonstration, lending significant political support to the MassHealth One Care program.

| Box 1: State Integrated Care and Financial Alignment Demonstrations for Dual Eligible Beneficiaries |

|---|

| State Integrated Care and Financial Alignment Demonstrations for Dual Eligible Beneficiaries are the product of the joint efforts of states and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services to develop more integrated ways to pay for and deliver health care to the more than 10 million seniors and younger people with disabilities who are eligible for both the Medicare and Medicaid programs. These individuals are among the poorest and sickest beneficiaries covered by either program. The demonstrations are an outgrowth of the Affordable Care Act and seek to test two new models (capitated and managed FFS) to align Medicare and Medicaid benefits and financing for dual eligible beneficiaries with the goal of delivering better coordinated care and reducing costs. |

Box 2 provides a timeline of key milestones in the implementation of the MassHealth One Care program, spanning from April 2011 to 2014. Following the CMS design contract award in April 2011, Massachusetts initiated a multi-agency collaboration with diverse stakeholders to develop a service delivery model, submitted to CMS in February 2012. In June 2012, MassHealth issued a Request for Responses (RFR) to gauge interest among health plans in forming capitated managed care entities, initially termed Integrated Care Organizations, now known as One Care plans. Ten health plans responded to the RFR, and a state agency committee selected six plans for further discussions. These plans also submitted applications to CMS. Massachusetts engaged in extensive negotiations with CMS to finalize the financial and benefit aspects of One Care, culminating in the MOU signed in August 2012. The MOU stipulated joint CMS and state responsibility for selecting and monitoring participating health plans. CMS aimed for savings through enhanced care coordination and efficiency across all Financial Alignment Initiative demonstrations, including MassHealth One Care program. Developing universally applicable rules and approaches across state demonstrations was another key CMS objective. A core purpose of the demonstration is to rigorously test the impact of an integrated care delivery system and a blended capitated payment model for serving both community and institutional dual eligible populations in Massachusetts.

| Box 2: Implementation Timeline of Duals Financial Alignment Demonstration in Massachusetts |

|---|

| – April 2011 – CMS awards design contracts to 15 states for new service and delivery models for dual-eligible population – February 2012 – Massachusetts submits Duals Demonstration Proposal to CMS – June 2012 – Massachusetts initiates Request for Responses from One Care plans – August 2012 – CMS and Massachusetts sign Memorandum of Understanding – July 2013 – CMS, Massachusetts, and the three participating One Care plans execute three-way contract – October 2013 – Active enrollment begins – January 2014 – First wave of passive enrollment begins – April 2014 – Second wave of passive enrollment begins – July 2014 – Third wave of passive enrollment begins – November 2014 – Fourth wave of passive enrollment begins for one plan only (Tufts Health Unify) |

In July 2013, three-way contracts were executed by CMS, Massachusetts, and the three selected health plans. Notably, three of the initial six plans identified through the RFR process opted out of participating in the MassHealth One Care program. A primary concern for these plans was the significant upfront investment required to build the necessary infrastructure and develop a comprehensive care delivery model. This included establishing a robust provider network capable of meeting the complex care needs of the dual eligible population within the agreed financial framework. Stakeholders acknowledged that this decision was challenging for these plans, given their prior investment and commitment to the demonstration’s goals. Following the contract signings, the three participating plans – Commonwealth Care Alliance, Fallon Total Care, and Tufts Health Unify (formerly Network Health) – underwent a joint CMS/MassHealth readiness review to prepare for the October 1, 2013 launch.

Specific dual eligible beneficiary categories were excluded from the MassHealth One Care program. These exclusions included individuals with other comprehensive public or private insurance, those in Intermediate Care Facilities for individuals with Intellectual Disabilities, and participants in Section 1915(c) home and community-based services (HCBS) waiver programs. However, Massachusetts beneficiaries enrolled in Medicare Advantage or the Program of All-inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE) could choose to participate in One Care if they disenrolled from their existing programs. Many stakeholders expressed hope for future inclusion of HCBS waiver participants in One Care. While initial considerations included this population, HCBS waiver participants were ultimately excluded from the MOU due to CMS concerns about service and payment duplication and the complexities of integrating care for this group with high service needs. Consumer advocates also supported this phased approach, suggesting that incorporating HCBS waiver participants after the program had established a solid track record and resolved initial transitional challenges would be more prudent. Advocates emphasized the high service needs of HCBS waiver participants and their reliance on these programs for independent living, making any transition-related risks a significant concern. One advocate also cautioned that rate adjustments would be necessary before extending the demonstration to HCBS waiver participants.

A consistently highlighted feature of the MassHealth One Care program‘s planning phase was the inclusive and transparent process fostered by MassHealth leadership. Stakeholders were particularly impressed by MassHealth’s commitment to communication, information sharing, and participatory decision-making. One stakeholder described the public planning process for One Care as the most collaborative and transparent they had witnessed in their extensive policy experience, citing it as an exemplary model for managing policy change effectively. Box 3 summarizes the key features of the Massachusetts demonstration, highlighting its targeted approach and innovative elements.

| Box 3: Highlights of Massachusetts One Care Duals Financial Alignment Demonstration |

|---|

| – Serves full benefit dual eligibles ages 21-64 in nine Massachusetts counties (one with partial coverage) – Delivers care through three One Care plans that provide patient-centered care through tailored care coordination teams – Includes an Independent Living Long-Term Services and Supports (LTSS) Coordinator on the enrollee’s care team, if the enrollee desires. These LTSS coordinators are from community-based organizations independent from health plans. – Includes behavioral health diversionary services not previously available to dual eligibles. These services were added to One Care to provide services to the approximately 70% of Massachusetts dual eligibles with a behavioral health condition. – Involves two types of enrollment: passive enrollment and active enrollment. Passive enrollment, occurring in four waves to date, allows for opt-out at any time and only occurs in counties where there is more than one plan. |

One Care Financial Model: A Capitated Approach

The MassHealth One Care program operates under a capitated financial model. One Care plans receive a per member, per month global capitation payment designed to cover all healthcare costs for enrolled beneficiaries. This comprehensive payment integrates Medicare and Medicaid funding streams, comprising three monthly components: a CMS payment for Medicare Parts A and B services, risk-adjusted using the CMS Hierarchical Condition Category (CMS-HCC) model; a second CMS payment for Medicare Part D prescription drug services, risk-adjusted using the RxHCC model; and a third payment from MassHealth, based on the beneficiary’s assigned rating category. A key concern raised by stakeholders was the potential inadequacy of the CMS rate portion, derived from CMS-HCC and RxHCC models, to accurately reflect the healthcare needs of the under-65 population served by One Care. This concern stemmed from the fact that CMS’s rate calculation was based on the entire dual eligible population, despite the age-variable inclusion in CMS-HCC and RxHCC models intended to account for age-related Medicare spending variations.

Upon the MassHealth One Care program‘s implementation in 2013, four MassHealth rating categories were in place, as outlined in the left panel of Box 4. Initial experiences and stakeholder feedback led to an expansion of these categories to better address the needs of particularly high-cost beneficiaries within the C2 and C3 community rating categories. Starting in 2014, these categories were further subdivided to differentiate between higher-cost beneficiaries and others within the same broader categories, as shown in the right panel of Box 4.

| Box 4: One Care Rating Category Definitions |

|---|

| 2013 One Care Rating Category Definitions |

| F1 (facility-based care): used for individuals residing in a long-term care facility for more than 90 days . C3: used for individuals who have either a daily skilled need, two or more Activities of Daily Living (ADL) limitations AND a need for three days of skilled nursing care per week, or four or more ADL limitations . C2: used for individuals with a chronic behavioral health diagnosis with a high level of service need . C1: used for individuals who do not meet criteria for F1, C3, or C2. |

| SOURCE: One Care: MassHealth plus Medicare – January Enrollment Report, MassHealth. January 2014. Available at http://www.mass.gov/eohhs/docs/masshealth/onecare/enrollment-reports/enrollment-report-january2014.pdf |

Beneficiary assignment to an initial MassHealth rating category is based on historical Medicaid claims data. This assignment can be adjusted based on information from an in-person Minimum Data Set – Home Care (MDS-HC) assessment, conducted by a registered nurse, often in conjunction with the Comprehensive Assessment. MassHealth rates incorporate a prospective reduction reflecting anticipated savings compared to historical claims. Initially, no savings were assumed from October 1, 2013, to March 31, 2014. A 1% savings assumption was applied from April 1, 2014, to December 31, 2014. For the second demonstration year (2015), a 0.5% savings assumption was used, and for the third year (2016), a 2% savings assumption was implemented. These savings targets were adjusted from the original MOU, reflecting a slightly lower savings expectation than initially projected.

The three-way contract terms established risk-sharing between CMS, the state, and One Care plans during the demonstration’s first year to facilitate the transition to global capitation. For subsequent years, risk sharing was initially eliminated. However, contract revisions in September 2014 reintroduced risk corridor protections for demonstration years 2 and 3. Additionally, to mitigate financial risk for One Care plans throughout the demonstration, the state implemented high-risk pools for exceptionally high-cost beneficiaries in the F1 and C3 rating categories during Years 2 and 3.

Finally, CMS and the state withheld a portion of the Medicare A/B and Medicaid capitation payments – 1% in year one, 2% in year two, and 3% in year three. One Care plans could earn back these withheld funds by meeting specific quality standards outlined in the contract. Year 1 withholds were based on process-focused performance measures, ensuring plans established fundamental care processes. These measures included establishing consumer governance boards, completing initial in-person care assessments within 90 days of enrollment for new beneficiaries, and complying with centralized beneficiary record requirements. In years 2 and 3, withhold payments were tied to performance on nine quality measures: all-cause readmissions, annual flu vaccines, follow-up after hospitalization for mental illness, depression screening and follow-up, blood pressure control, medication adherence for oral diabetes medications, initiation and engagement of alcohol and other drug dependence treatment, timely transmission of transition records, and beneficiary-reported quality of life.

One Care Service Delivery Model: Integrated and Person-Centered

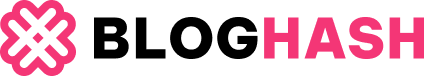

The MassHealth One Care program‘s service delivery model, detailed in the February 2012 CMS proposal, emphasizes an integrated and person-centered approach. Massachusetts engaged diverse stakeholders to develop a comprehensive benefit package tailored to the needs of the under-65 dual eligible population with disabilities. The model comprises an initial assessment followed by integrated services delivered through a care coordination team. This team includes a care coordinator, primary care, behavioral health, and LTSS providers, an LTSS coordinator, peer support/counseling, specialized service providers, and any other individuals the beneficiary chooses to include.

Figure 1: MassHealth One Care Program Care Coordination Team Structure: Illustrates the integrated team approach with the beneficiary at the center, surrounded by care coordinator, primary care provider, behavioral health provider, LTSS provider, LTSS coordinator, peer support, and family/caregivers.

Initial Assessment: Understanding Beneficiary Needs

Within 90 days of enrollment in a MassHealth One Care program plan, a mandatory face-to-face initial assessment must be completed. These assessments are conducted at a location chosen by the beneficiary, including their home if preferred. The assessment’s purpose is to gather detailed information about the beneficiary’s healthcare and support requirements and to understand their personal goals. The assessment covers twenty key domains, including: immediate needs and current services, health conditions, medications, communication abilities, functional status (ADL and IADL limitations), mental health and substance use, personal goals, accessibility needs, equipment needs, transportation access, housing and home environment, employment status, involvement with other care coordinators or agencies, informal and caregiver supports, abuse and neglect risk factors, leisure and community involvement, social supports, food security and nutrition, wellness and exercise, and advance directives/guardianship.

One Care plans are responsible for conducting these assessments, though subcontracting to providers is permitted. Typically, One Care plan care coordinators, often nurses, conduct these initial assessments. Following the initial comprehensive assessment, subsequent assessments are required at least annually or upon significant beneficiary changes.

Early implementation revealed that some beneficiaries required placement in higher rating categories than initially assigned, primarily shifting from C1 to C2. MassHealth acknowledged this issue and compensated plans for the difference between assessed and proxy rating categories for up to three months prior to the assessment date. One plan estimated that 20-30% of initial C1 assignments were later reclassified as C2 or C3. Another plan reported a higher estimate, around 40%. Furthermore, some stakeholders noted challenges for One Care plans in locating and scheduling initial assessments, delaying timely rating category adjustments. To address this, one plan reported utilizing pharmacy information to contact beneficiaries and schedule assessments, as pharmacy records often contain accurate contact details.

Care Coordination: The Cornerstone of One Care

Drawing upon Massachusetts’ prior successful care coordination initiatives, although none previously focused on the under-65 dual eligible population, care coordination is central to the MassHealth One Care program. Consistent with the program’s person-centered and coordinated care goals, each beneficiary is assigned a care coordinator. This individual serves as a key member of the beneficiary’s interdisciplinary care team, as depicted in Figure 1, collaborating to develop a Personal Care Plan.

Community Support Services and LTSS Coordination

A critical aspect of the MassHealth One Care program was the need for plans to develop a robust LTSS infrastructure, an area where health plans historically had limited experience. Concerns were raised about the absence of upfront financial resources for these start-up activities and the potential for managed care organizations to reduce LTSS access or misunderstand how to integrate these services.

In response, Massachusetts incorporated the role of an LTSS coordinator into the service delivery model, structured to be independent of the health plan. One Care plans contract with community-based organizations to staff these positions under various financial arrangements. During the initial assessment and care plan development, beneficiaries are offered the option to include an LTSS coordinator on their care team.

Significant attention was devoted to defining the LTSS coordinator’s role to ensure clarity and effective utilization by both plans and beneficiaries. As defined in the MOU, the LTSS coordinator, contracted by the One Care plan with a community-based organization, provides independent support to enrollees, assisting with LTSS needs coordination and offering expertise and community support to both the enrollee and their care team. The LTSS coordinator acts as an independent facilitator and liaison between the enrollee, the plan, and service providers. LTSS coordinators must be offered to beneficiaries in the C3 (including C3A and C3B) and F1 rating categories during assessments, as well as to beneficiaries in other categories who request it. They must also be available upon beneficiary request, when community-based LTSS needs are identified, for beneficiaries receiving targeted case management or rehabilitation services from the Department of Mental Health, or in the event of contemplated institutional admissions.

Stakeholders frequently highlighted the LTSS coordinator concept as a particularly novel and challenging aspect of MassHealth One Care program planning and early implementation, representing largely uncharted territory. Concerns included potential service duplication and inefficiencies if beneficiaries had too many coordinators, necessitating a “coordinator for the coordinators.” Initial capacity concerns due to insufficient coordinator numbers and potential conflicts of interest with coordinators employed by service agencies were also noted. The contract specifically restricts most service agencies from filling this role, except with a waiver from the One Care plan (e.g., to address network adequacy), and no waivers had been requested to date. Conversely, consumer advocates emphasized the LTSS coordinator’s potential to provide beneficiaries with crucial guidance and support in navigating the care system, making One Care more attractive. The role’s potential to offer an independent voice for beneficiaries within the care team was also recognized by consumer advocates. Stakeholders noted that LTSS coordinators could alleviate burdens on informal caregivers by providing beneficiaries with dedicated points of contact for care management assistance.

Behavioral Health Services Integration

MassHealth estimated that approximately 70% of potential MassHealth One Care program beneficiaries had a behavioral health diagnosis, making robust behavioral health service integration paramount. The care coordination team structure inherently supports integrated physical and behavioral healthcare within a capitated payment model. Furthermore, Massachusetts actively worked to include diversionary behavioral health services within One Care, mirroring services already available to other Medicaid beneficiaries in the state. These services encompass crisis stabilization, Program of Assertive Community Treatment (PACT), community support programs, partial hospitalization, acute treatment services and clinical support services for substance abuse, psychiatric day treatment, intensive outpatient services, structured outpatient addiction programs, and emergency services (see Box 5 for a detailed list). This inclusion ensured that dual eligible beneficiaries under 65 received behavioral health benefits comparable to the broader Medicaid population in Massachusetts. Consumer advocates also stressed the importance of a recovery-oriented approach to behavioral health services within One Care. Beneficiaries can collaborate with their care coordinators to access community support programs and other services facilitating community-based behavioral healthcare.

Additional One Care Supplemental Benefits

Beyond the core services, the MassHealth One Care program offers expanded Medicaid state plan services, including improved access to durable medical equipment, restorative dental services, and personal care encompassing cueing and supervision. Additional supplemental benefits include respite care, care transitions assistance, home modifications (including installation), community health workers, medication management, non-medical transportation, and the elimination of prescription copays (see Box 5 for a comprehensive list). Stakeholders noted that the absence of prescription copays, coupled with enhanced dental services and benefits such as glasses and hearing aids, were significant factors in beneficiaries’ voluntary enrollment decisions.

| Box 5: Supplemental Benefits in the One Care Demonstration |

|---|

| Diversionary Behavioral Health Services: |

| – community crisis stabilization – community support program – partial hospitalization – acute treatment services for substance abuse – clinical support services for substance abuse – psychiatric day treatment – intensive outpatient program – structured outpatient addiction program – program of assertive community treatment – emergency services program |

| SOURCE: Massachusetts’ Demonstration to Integrate Care and Align Financing for Dual Eligible Beneficiaries Executive Summary, Kaiser Family Foundation Policy Brief, October 2012, Available at https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/massachusetts-demonstration-to-integrate-care-and-align/ |

Enrollment Dynamics in One Care

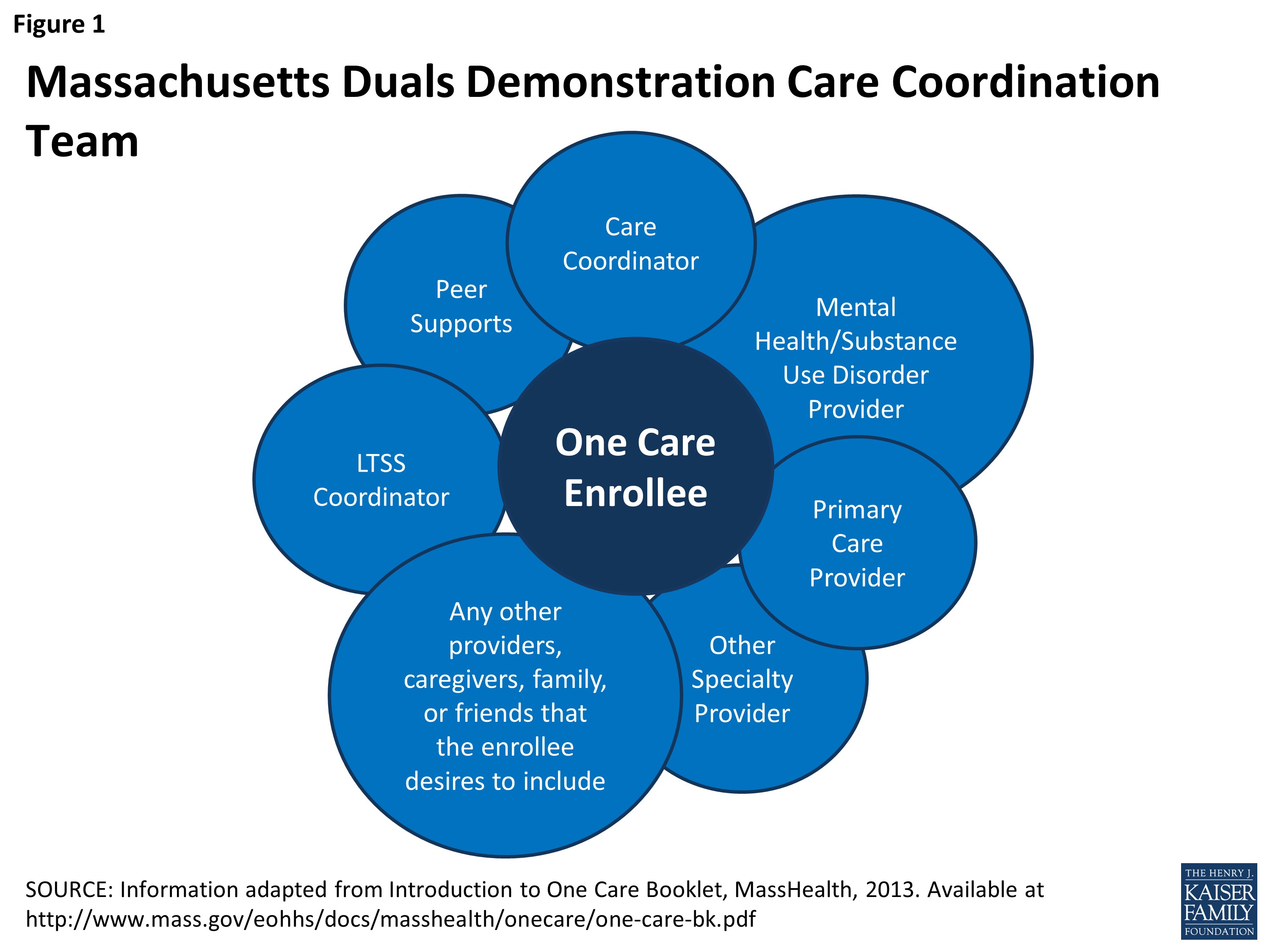

Enrollment in the MassHealth One Care program commenced on October 1, 2013, across nine of Massachusetts’ fourteen counties (Figure 2). In five counties (Essex, Franklin, Middlesex, Norfolk, and parts of Plymouth County), only a single plan operated, necessitating an active “opt-in” enrollment process.

Figure 2: MassHealth One Care Program Coverage Map: Illustrates the nine Massachusetts counties participating in One Care, differentiating between active “opt-in” enrollment counties (single plan availability) and passive enrollment counties (multiple plan availability).

Conversely, in the remaining four counties (Hampden, Hampshire, Suffolk, and Worcester), where two or more plans were available, dual eligible beneficiaries who did not actively opt-out or select a plan were subject to auto-assignment to a One Care plan. Self-selection remained an option at any time. Enrollment changes, including plan switches, took effect on the first day of the following month. Individuals who opted out retained the option to opt back in at any point.

By February 2015, the MassHealth One Care program had enrolled 17,763 beneficiaries, representing 18.4% of the estimated 96,449 eligible state residents. This enrollment comprised both opt-in and passively enrolled individuals. To date, 26,792 individuals had opted out through various means: refusing passive enrollment, proactively declining participation in opt-in counties, or disenrolling after initial enrollment.

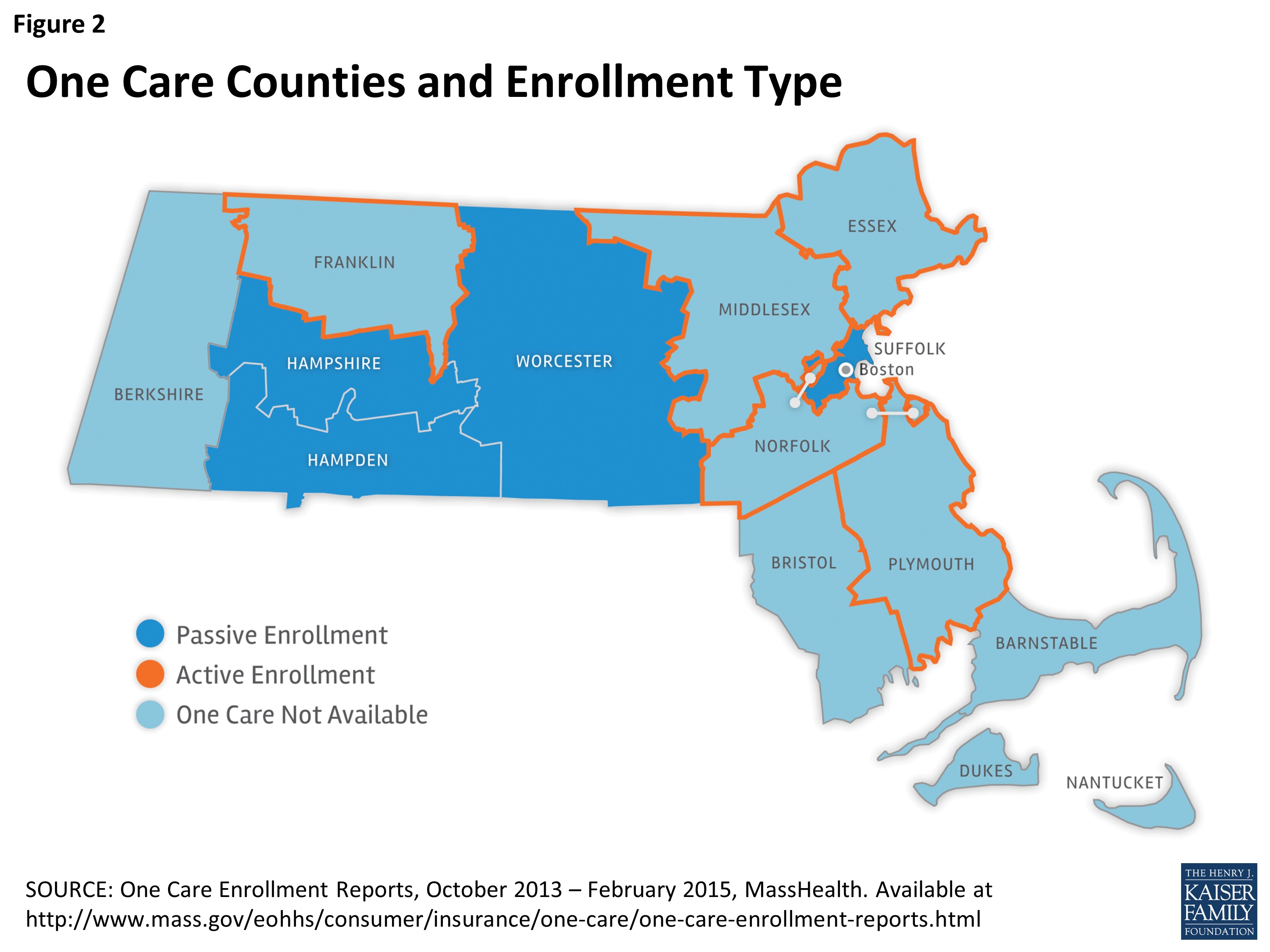

Figure 3 illustrates enrollment trends by month, both overall and by participating plan. As of February 2015, two plans accounted for over 89% of total enrollment, reflecting the counties in which they operated. Commonwealth Care Alliance held 57% of enrollment, Fallon Total Care 32%, and Tufts Health Unify 11%.

Figure 3: MassHealth One Care Program Enrollment Growth Chart: Depicts monthly enrollment trends from October 2013 to February 2015, showing overall growth and enrollment distribution across Commonwealth Care Alliance, Fallon Total Care, and Tufts Health Unify plans.

Of the 17,763 beneficiaries enrolled across the nine counties, approximately 63% were passively enrolled, and 37% actively enrolled. In the four passive enrollment counties, 30% of eligible beneficiaries had enrolled (passively or actively), 38% had opted out, and 32% remained eligible for future passive enrollment waves without having opted in or out. Suffolk County, including Boston and the sole passive enrollment county in eastern Massachusetts, exhibited the lowest opt-out rate (24%) among passive enrollment counties. In the five active enrollment counties, nearly 7% of dual eligible beneficiaries had actively enrolled in One Care, 18% had actively opted out, and 75% remained in the state’s FFS system. All One Care beneficiaries can opt out monthly and subsequently opt back in. Beneficiaries enrolled in One Care upon turning 65 and remaining MassHealth eligible are offered the choice to stay in One Care, select a PACE or SCO plan if available, or revert to the FFS system.

Passive Enrollment Process and Considerations

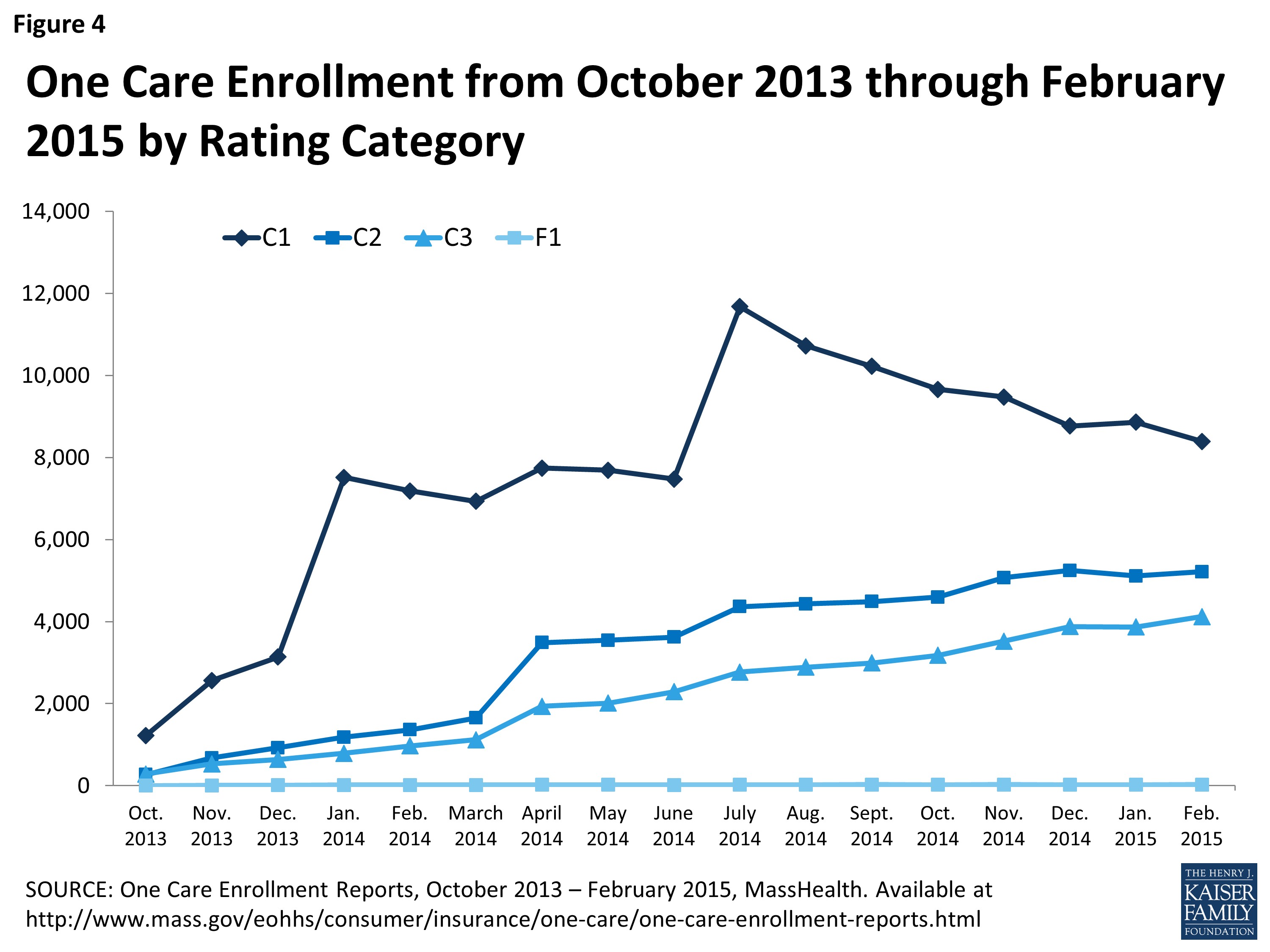

Four passive enrollment waves had occurred to date: January, April, and July 2014, and a smaller wave in November 2014 focused on Tufts Health Unify. Tufts Health Unify did not participate in the April 2014 passive enrollment wave, and the November wave aimed to align its enrollment more closely with initial projections. Figure 4 shows monthly enrollment by rating category over the demonstration’s first 17 months.

Figure 4: MassHealth One Care Program Enrollment by Rating Category: Illustrates the distribution of enrollees across different rating categories (F1, C3, C2, C1) from October 2013 to February 2015, providing insights into the program’s reach across different needs-based categories.

MassHealth employed an “intelligent assignment” approach for passive enrollment, prioritizing pre-existing provider relationships. A passive enrollment assignment expert, rather than a computer algorithm, used claims data to match beneficiaries with One Care plans already contracting with their existing providers. For C1 category beneficiaries, assignment prioritized matching primary care providers. For C2 beneficiaries, both primary care and behavioral health providers were matched. For C3 beneficiaries, primary care and LTSS providers were prioritized.

While generally viewed as effective, the passive enrollment process faced criticism from some provider and consumer stakeholders. Concerns arose that passive enrollment overwhelmed some plans, struggling to locate and assess large numbers of newly enrolled beneficiaries. One consumer advocate argued for an entirely opt-in enrollment approach. However, passive enrollment was considered essential by others to provide One Care plans with necessary revenue and build infrastructure for care coordination and service delivery. One health plan suggested monthly passive enrollment, rather than quarterly waves, to distribute beneficiary influx more evenly, aiding engagement and needs planning. Another stakeholder noted that passive enrollment pressures hindered thoughtful LTSS coordinator function implementation. Challenges in maintaining existing provider relationships were cited as reasons for opting out, alongside fear of change and wait-and-see attitudes among dual eligible beneficiaries.

Public Awareness and Marketing Strategies for One Care

Public outreach for the MassHealth One Care program began in July 2013, with health plan marketing starting in September 2013. One Care plans were required to obtain prior approval from CMS and Massachusetts for specific marketing and beneficiary communication materials. The state conducted public informational meetings across different regions from July to October 2013. For passively enrolled beneficiaries, 60- and 30-day notices were mailed, informing them of impending plan assignment and their rights to choose a different plan or opt out. Workgroups involving state agency staff and stakeholders developed these member notices, with input from the Department of Mental Health to ensure inclusive and recovery-oriented language. Enrollment guides and decision forms accompanied these notices. Online enrollment was not offered; beneficiaries could enroll by mail or phone.

Early challenges included ensuring beneficiary awareness of One Care. Issues included incorrect addresses, difficulties contacting homeless or at-risk beneficiaries, and explaining One Care benefit differences to PACE or Medicare Advantage enrollees. The SHINE Program (Serving Health Insurance Needs of Everyone), a state health insurance assistance program, played a crucial role in counseling beneficiaries about One Care options. SHINE volunteers, experienced in advising elders on Medicare plans, were trained to address concerns of non-elderly individuals with disabilities. Outreach highlighted new services like care coordination, dental, and vision benefits. MassHealth focused on direct outreach through meetings and forums and emphasized word-of-mouth. Simultaneous rollout of multiple ACA initiatives created some beneficiary confusion. No campaigns discouraging One Care enrollment were reported.

Communication challenges were addressed through new materials and approaches. For example, initial Medicare Part D disenrollment notices, arriving before One Care enrollment information, caused confusion. SHINE counselors educated beneficiaries and provided feedback, leading to timed enrollment notices and a “One Care Covers Prescription Drugs” insert in enrollment packets. SHINE feedback, beneficiary input, and stakeholder insights informed these improvements.

Ongoing efforts to boost enrollment include video vignettes featuring beneficiary experiences to raise awareness about MassHealth One Care program.

Provider Network Development and Involvement in One Care

Each MassHealth One Care program plan must annually demonstrate an adequate provider network across medical, behavioral health, pharmacy, community-based services, and LTSS needs, ensuring physical, communication, and geographic access. Plans invested significant effort in developing broad provider networks. The Massachusetts demonstration contract, consistent with all demonstrations, included ADA compliance requirements. MassHealth mandates contracts with providers demonstrating commitment to accommodating physical access and flexible scheduling needs. This includes designated ADA compliance officers and work plans for physical accessibility. Plans must also provide continuing education on ADA compliance and accessibility to their provider networks.

One Care plan contracts include detailed network adequacy requirements to ensure continuity of care. Provider network approval was part of the readiness review, meeting or exceeding Medicare and MassHealth network adequacy standards. Primary care continuity was a specific issue. While Medicaid claims identified primary care providers, this information was not collected on enrollment forms. Some providers declined to join One Care networks or opted for exclusive networks. Conversely, some providers requested to join networks upon learning of enrolled patients.

Many new contracting partnerships emerged under One Care, including transportation vendors and community-based organizations for day programs and adult foster care. Plans invested in training and education to help external organizations understand the care coordination model. New personnel, like outreach workers and psychiatric nurse practitioners, were added to care coordination teams. Single-case out-of-network agreements were offered to providers with pre-existing relationships with beneficiaries willing to serve beneficiaries at in-network rates but unwilling to join the network. However, single-case arrangements proved challenging due to provider group organization in Massachusetts.

Beneficiary Engagement and Empowerment in One Care

Massachusetts has a strong tradition of beneficiary engagement in healthcare initiatives, and the MassHealth One Care program is no exception. Beneficiary involvement in design and implementation has been a hallmark, occurring at multiple levels. The state’s robust disability and behavioral health consumer advocacy communities were actively engaged in discussions and decision-making. MassHealth involved beneficiary stakeholder organizations early in the planning process, incorporating their input into service delivery model design, oversight structure, and grievance/appeals processes. During program design, input was sought from cross-disability and disability-specific consumer perspectives. In 2011, MassHealth conducted focus groups with 40 dual eligible beneficiaries to ensure diverse representation. Outreach sessions with beneficiaries with specific disabilities were also conducted. Stakeholders emphasized the essential role of this process in shaping the care delivery model and CMS demonstration proposal. For instance, beneficiary feedback on confusing communications led MassHealth to prioritize improved plan communication. Concerns about dental service access resulted in service expansions under the demonstration.

An Implementation Council, established by MassHealth, monitors program access, quality, transparency, and ADA compliance. The council, with up to 21 members, receives support from the University of Massachusetts Medical School (UMMS). Members were selected through an open nomination process, with at least half being MassHealth beneficiaries with disabilities or family members. Remaining slots were filled by hospital, provider, and advocacy organization representatives. The Implementation Council, led by a Chair and Co-Chairs, holds monthly public meetings, providing formal feedback to the state on implementation progress and issues. One Care plans have also established beneficiary advisory bodies for firsthand feedback and improvement identification. One plan described inviting beneficiaries to join councils, providing transportation, and experiencing strong attendance from beneficiaries, caregivers, and advocates.

The Implementation Council, MassHealth, and UMMS formed the Early Indicators Project (EIP) workgroup in October 2013 to monitor and report on early beneficiary experiences with MassHealth One Care program. The EIP uses focus groups, surveys, enrollment data, and feedback from SHINE and One Care plans to assess member experience and enrollment drivers. Data is publicly available on the MassHealth website, including monthly enrollment data, customer service reports, focus group/survey reports, and quarterly reports.

An Ombudsman program, established in March 2014, assists One Care beneficiaries with concerns or conflicts, acting as a bridge between beneficiaries and the Executive Office of Elder Affairs. The Ombudsman program, selected through an RFP process, is a partnership between the Disability Policy Consortium and Health Care for All. It manages a network with regional, language-based, and disability-based capabilities, interacting with the Implementation Council and presenting to workgroups. Timely initial assessments have been a primary issue raised with the Ombudsman. While causing frustration, few beneficiaries disenrolled due to assessment timeliness. It remains too early to assess beneficiary navigation of appeals processes for service authorization decisions, as few appeals had been initiated. A broader issue for the Ombudsman program’s future is developing tools beyond plan outreach to address beneficiary concerns.

Performance Measurement and Outcome Assessment for One Care

Quality Metrics and Reporting Framework

The August 2012 MOU mandates One Care plans to report on 104 core quality metrics, covering access, care coordination, health and well-being, behavioral health, patient experience, screening, prevention, and quality of life. These metrics include CMS core measures (Medicare Advantage and Part D), Massachusetts-specific measures, and combined measures. Reporting includes NCQA/HEDIS, Health Outcomes Survey (HOS), and Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) measures, and LTSS performance. A subset of these metrics informs withhold payments across the three demonstration years. Stakeholders raised concerns about the sheer volume of measures, questioning plans’ capacity to meaningfully improve across so many domains. Concerns were also voiced about the appropriateness of some measures as indicators of beneficiary care needs being met. For example, some stakeholders noted a lack of robust behavioral health performance metrics relevant to the MassHealth One Care program population.

Outcomes Evaluation and Future Impact

Savings from the MassHealth One Care program are anticipated primarily from reduced emergency department and inpatient utilization, both for medical and behavioral health needs. Care coordination and increased reliance on intermediate care levels are seen as key drivers of these reductions. Multiple evaluation approaches are being used to assess program success in achieving these and other outcomes. MassHealth actively tracks and reports internal data to evaluate program impact. Early data from focus groups and consumer surveys through the EIP provide initial insights but are not designed for comprehensive assessment. CMS has contracted an independent evaluator to assess the impact of all state dual eligible demonstrations, including One Care, on cost, quality, utilization, and beneficiary experience using mixed-methods approaches. Qualitative data will come from site visits, focus groups, and interviews. Quantitative analysis will assess broader demonstration impact, including savings calculation using comparison groups.

A tension exists between beneficiaries’ and advocates’ desire for early performance data and the fact that even preliminary quantitative assessments of quality, cost, and well-being impacts are years away. Stakeholders did not expect inpatient and emergency department use and spending impacts to be discernible for at least another year post-implementation.

Concerns regarding achieving measurable inpatient and emergency department cost reductions include rate sufficiency for the comprehensive One Care benefit package and lack of upfront funding for infrastructure development, particularly crisis stabilization services. Rate adequacy, especially for C2 beneficiaries with chronic behavioral health conditions, remains uncertain. One Care plans highlighted the difficulty of funding upfront infrastructure development under current rates, even if rates prove sufficient long-term. Both the state and plans recognized the initial model implementation should focus on counties with sufficient dual eligible beneficiaries to effectively target infrastructure development. Limited crisis stabilization service capacity in most One Care communities was cited as a concern, potentially leading to costly inpatient placements for beneficiaries needing crisis care, jeopardizing the financial model’s viability.

Future Directions and Key Learnings from One Care

Early implementation insights from MassHealth One Care program, the first dual eligible capitated financial alignment demonstration, offer valuable lessons for other states. Challenges noted by Massachusetts stakeholders include securing robust health plan participation under negotiated financing terms, passive enrollment complexities (locating beneficiaries, timely assessments), identifying and engaging beneficiaries’ existing providers, and refining capitation rates and risk adjustment. Implementing the LTSS coordinator role and establishing adequate provider networks across care domains also presented challenges. While transitional issues are expected in new programs, consumer advocates emphasized the risks these issues posed to vulnerable dual eligible beneficiaries reliant on well-functioning care teams for independent living.

Stakeholder interviews also highlighted program strengths. The state’s commitment to stakeholder engagement and passive enrollment’s role in ensuring plan financial stability were noted positively. MassHealth leadership’s open, participatory, and transparent approach to design and implementation was widely praised. One provider stakeholder emphasized the unprecedented thoughtfulness and openness of the state’s planning process, extending into implementation with public meetings and Implementation Council engagement.

The Massachusetts experience raises broader questions about effectively transitioning vulnerable populations to capitated payment and integrating Medicaid and Medicare financing. Enhanced care coordination and flexible resource allocation benefits have been immediately apparent for some MassHealth One Care program beneficiaries. Longer-term evaluation is needed to assess other key aspects. Comparing multi-phased passive enrollment to slower active enrollment, and reflecting on initial statewide participation goals versus infrastructure investment realities are crucial. Extending One Care to non-participating counties is not currently planned. One stakeholder noted the regional expansion approach aligned better with a demonstration’s spirit. Long-term financial model viability and the program’s ability to reduce inpatient and emergency department costs and improve care quality require ongoing assessment.

In summary, stakeholder interviews conveyed cautious optimism about the MassHealth One Care program‘s potential to transform care for dual eligible beneficiaries in Massachusetts. While implementation concerns exist, broad agreement acknowledges the prior system’s inadequacies and the timeliness of investing in improved care delivery and financing models for this population.

This issue brief was prepared by Colleen Barry of Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and Lauren Riedel, Alisa Busch, and Haiden Huskamp of Harvard Medical School.

Executive Summary