California’s Medicaid program, known as Medi-Cal, stands as the largest state Medicaid program in the United States. Providing health insurance to almost one-third of California’s population of over 38 million residents, Medi-Cal is a critical source of health coverage within the state. It serves as the primary coverage for low-income children, adults, and individuals with disabilities, and also offers supplementary coverage for many elderly Medicare beneficiaries in California.

For several decades, Medi-Cal has been evolving from a fee-for-service (FFS) payment and healthcare delivery model to a system that increasingly relies on risk-based managed care. In the FFS system, beneficiaries had the flexibility to consult any healthcare provider who accepted Medi-Cal, with providers being reimbursed for each service or consultation. Conversely, under managed care, the state enters into agreements with health plans to administer Medi-Cal benefits to enrollees. In return, the health plans receive a fixed monthly payment, known as a “capitation” payment, for each enrollee. These plans are then responsible and financially accountable for delivering the contracted healthcare services.

California holds the distinction of being the first state to experiment with managed care within Medicaid, initiating pilot programs in the early 1970s. The Medi-Cal managed care program has developed a distinctive structure, shaped by the diverse healthcare delivery and financing systems across different counties in the state. Over time, California has progressively transitioned more Medi-Cal beneficiaries into managed care. Today, it operates the largest Medicaid managed care program nationwide, with nearly 10 million children, adults, seniors, and people with disabilities—representing over three-quarters of all Medi-Cal beneficiaries—enrolled in managed care plans.

In its initial managed care pilot programs, California awarded contracts to health plans to provide services to Medi-Cal beneficiaries within specific counties or service areas. Gradually, the Department of Health Care Services (DHCS), which is California’s Medicaid agency, broadened the scope of its managed care program to include more counties. Subsequently, as part of the “California Bridge to Reform Demonstration,” a Section 1115 waiver approved by CMS in November 2010, the state extended mandatory managed care to include seniors and individuals with disabilities enrolled in Medi-Cal. California chose to expand Medi-Cal eligibility under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), significantly increasing the total number of Medi-Cal beneficiaries and those in managed care plans. As of July 2015, 77% of Medi-Cal beneficiaries were enrolled in Medi-Cal managed care plans, and by October 2015, this number exceeded 10 million beneficiaries. Furthermore, DHCS has partnered with the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to introduce a demonstration program in seven major counties. This program allows beneficiaries who are dually eligible for both Medicare and Medicaid to enroll in capitated managed care plans that encompass the full spectrum of services covered by both programs, including managed long-term services and supports (MLTSS).

As more states are increasing their use of risk-based managed care to serve their Medicaid populations, this analysis of California’s shift to a predominantly managed care-based Medicaid program is both timely and valuable for Medicaid stakeholders. It also highlights potential implications for Medi-Cal of CMS’ proposed rule on Medicaid managed care, a significant revision of current regulations expected to be finalized in Spring 2016.

Structure of Medi-Cal Managed Care Program

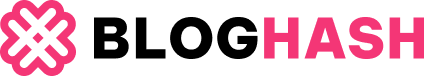

A notable characteristic of the Medi-Cal managed care program is the variety of managed care models implemented across different counties. These models (Figure 1) are significantly influenced by the historical roles of counties in financing and delivering primary care, public hospital services, mental health services, and certain long-term services and supports to residents who are poor or medically indigent. In the 1980s, the earliest Medi-Cal managed care programs emerged as County Organized Health System (COHS) plans. These included the Health Plan of San Mateo and Santa Barbara Regional Health Authority, operating under Section 1915(b) waivers. COHS plans were established by counties, with mandatory enrollment for almost all Medi-Cal beneficiaries within the county service area, including seniors and persons with disabilities, and covering nearly all Medi-Cal services. In the early 1990s, Medi-Cal expanded its managed care program by incorporating additional COHS plans, such as Partnership Health Plan serving Solano and Napa Counties, CalOptima serving Orange County, and Central California Alliance for Health serving Santa Cruz and Monterey Counties.

| Medi-Cal Managed Care Models |

|---|

| County Organized Health System (COHS). A health plan created and managed by a County Board of Supervisors. Within a COHS county, all managed care enrollees are in the same plan. (22 counties) |

| Two-Plan Model. This model includes a publicly-run entity (a “Local Initiative”) and a commercial plan. (14 counties) |

| Geographic Managed Care (GMC). In this model, DHCS contracts with a mix of commercial and non-profit plans that compete to serve Medi-Cal beneficiaries. (2 counties) |

| Regional Expansion Model. DHCS contracts with two commercial plans in each county. (18 counties) |

| Imperial Model. This model operates only in Imperial County where DHCS contracts with two commercial plans. |

| San Benito (Voluntary) Model. This model operates only in San Benito County where DHCS contracts with one commercial plan. |

Figure 1: Medi-Cal Managed Care Models, by County

The state also developed the Two-Plan Model, designed to transition substantial portions of the Medi-Cal population into managed care while protecting the role of traditional safety-net providers, and the Geographic Managed Care Model (GMC) in Sacramento and San Diego Counties. The Two-Plan Model offers enrollees a choice between a commercial plan and a “Local Initiative” public plan. Similar to COHS plans, Local Initiative plans are public entities and are expected to collaborate with county public hospitals and safety-net providers to support the safety-net delivery system. Generally, Two-Plan Model counties are those with large Medi-Cal populations and public hospital systems crucial to the safety-net, including nine of California’s 12 public hospital health system counties.

Local Initiative plans benefit from strong local support and typically capture a 65%-85% Medi-Cal market share, with commercial plans playing a less dominant role in their service areas. While there is only one Local Initiative plan per county, some subcontract with one or more commercial plans. This effectively offers Medi-Cal enrollees in these counties more than two plan options. For instance, L.A. Care, the Local Initiative plan in Los Angeles County, partners with Anthem Blue Cross, Care1st, and Kaiser Permanente, in addition to directly providing health plan services to enrollees.

The GMC Model utilizes a combination of commercial and non-profit health plans but does not include Local Initiative plans. Enrollees in GMC counties have access to more than two plan choices. Similar to COHS, enrollment in both the Two-Plan and GMC Models is mandatory for low-income adults and children. However, unlike COHS, enrollment in the Two-Plan and GMC Models was initially voluntary for seniors and persons with disabilities, becoming mandatory in 2012.

Lastly, the Regional Expansion, Imperial, and San Benito (Voluntary) Models were established when Medi-Cal extended managed care to rural areas in late 2013. Both the Regional Expansion and Imperial Models involve agreements with two commercial plans. When children in the Healthy Families Program—California’s Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP)—who were enrolled in Kaiser Permanente’s Healthy Families plan, transitioned to Medi-Cal coverage in 2013, the state contracted with Kaiser Permanente in three Regional Expansion Model counties to ensure continuous care for these children. The San Benito Model allows Medi-Cal enrollees in San Benito County to choose between FFS and the single contracted commercial plan.

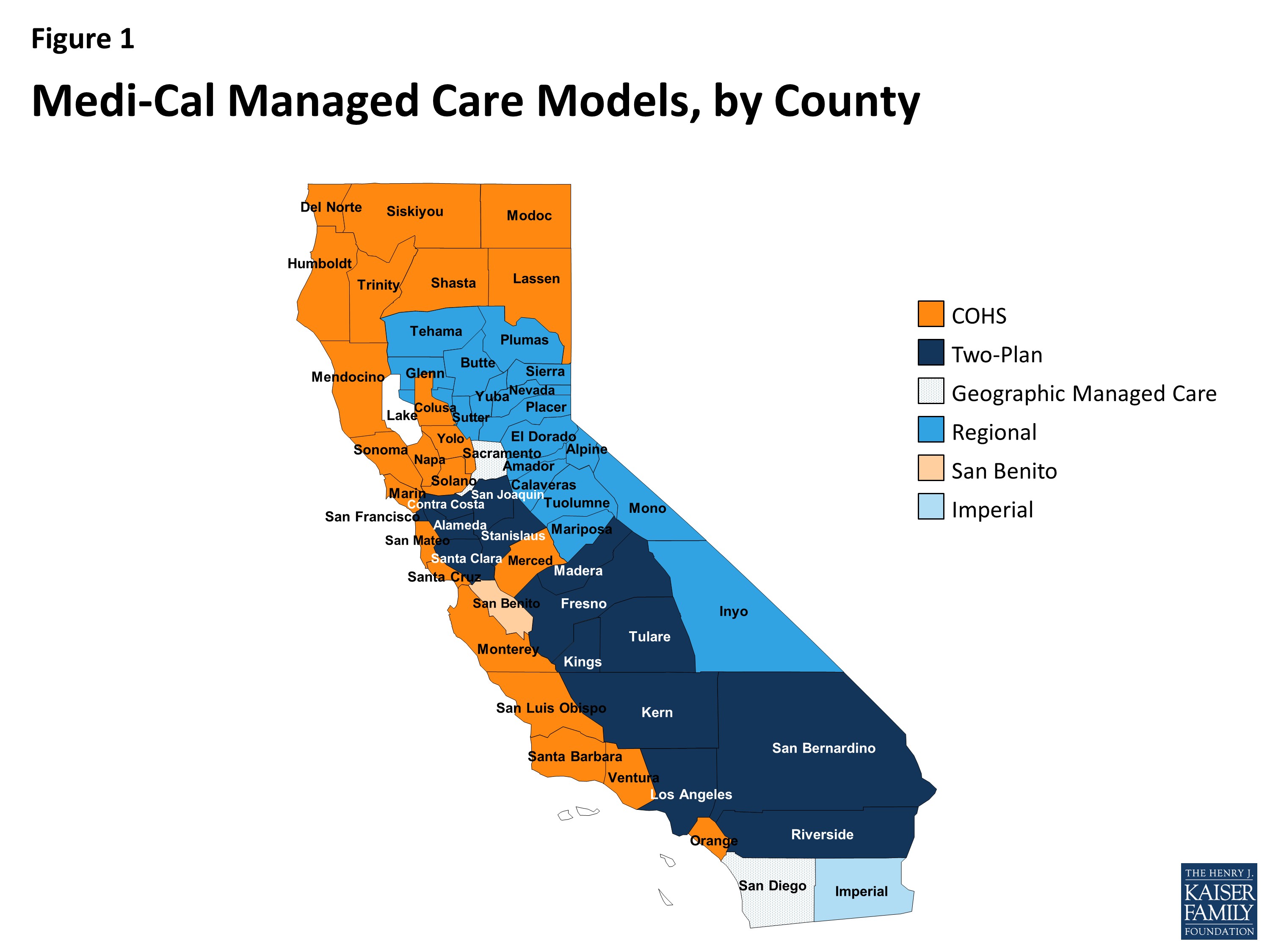

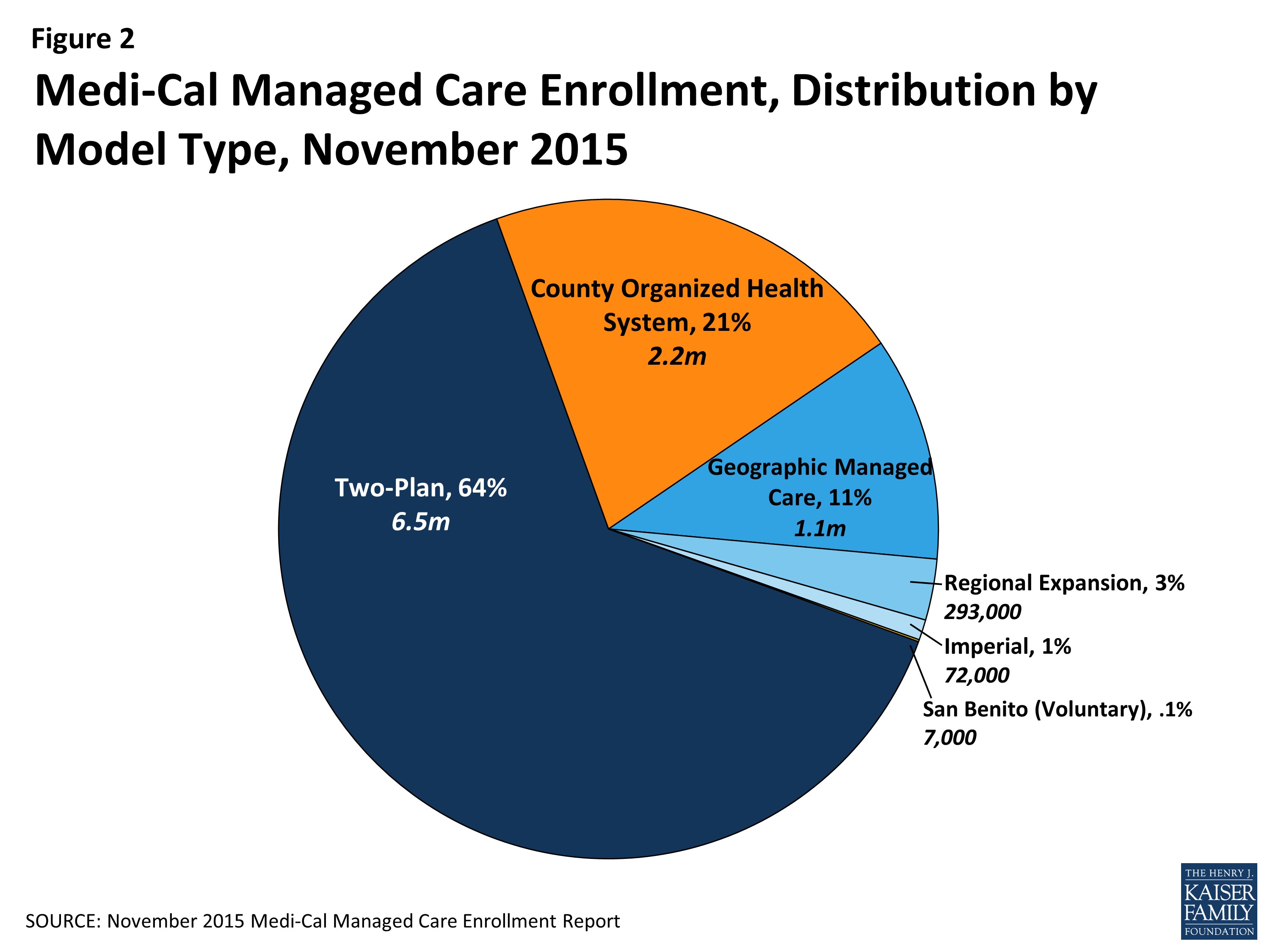

In total, six distinct managed care models are currently operational across California’s 58 counties. Reflecting population distribution across the state, the majority of Medi-Cal beneficiaries—nearly two-thirds as of October 2015 (64%)—were enrolled in the Two-Plan Model. An additional 21% were enrolled in the COHS Model, and 11% in the GMC Model (Figure 2). A significant majority of Medi-Cal managed care enrollees (68%) were served through local public plans (COHS plans and Local Initiative plans under the Two-Plan Model), while about one-third were served through commercial plans (Figure 3).

Figure 2: Medi-Cal Managed Care Enrollment, Distribution by Model Type, November 2015

Figure 3: Medi-Cal Managed Care Enrollment, Distribution by Plan Type, November 2015

Key Programmatic Dimensions of Medi-Cal Managed Care

Managed Care Plan Enrollment

Individuals can apply for Medi-Cal through various channels: by mail, in person, by phone via their County Social Services Office, or, since the ACA coverage expansions in 2014, online through the Covered California website (www.coveredca.com). Upon determination of eligibility, individuals are enrolled in Medi-Cal and receive a Benefits Identification Card. They then select from available health plan options or are automatically assigned to a plan if they do not make a selection. In COHS counties, a single plan manages Medi-Cal, and all enrollees are mandatorily enrolled in that plan. In San Benito County, where only one health plan is available, beneficiaries can enroll in that plan or opt to remain in Medi-Cal FFS.

Primary Care Provider Selection

Upon enrolling in a health plan, beneficiaries choose a primary care physician (PCP) within the plan’s network. If a PCP is not selected by the beneficiary, the health plan will assign one. Notably, California has specific regulations regarding PCP selection for adults newly eligible under ACA Medicaid expansion in the 12 counties with public hospital health systems. These systems previously served these adults through Low Income Health Programs and county indigent programs. Similar to other counties, Medicaid expansion adults in these counties either select or are auto-assigned a PCP by their health plan. However, to support county public hospital health systems, for the period between January 1, 2014, and December 31, 2016, plans were required to auto-assign at least 75% of newly eligible adults who did not select a PCP to a PCP within the county hospital health system. This requirement was in place until the system reached its enrollment target or notified the plan of reaching capacity. The required percentage decreased to 50% starting January 1, 2017. MCOs could avoid oversight action for not meeting the 75% auto-assignment standard if they could prove they attempted to meet it but were limited by regulatory geographic access standards.

Benefits and Carve-Outs

Medi-Cal offers comprehensive primary and acute care, behavioral health care, and long-term services and supports (LTSS) to its beneficiaries. While most primary and acute care benefits for managed care enrollees are provided by the managed care plans, certain services are generally “carved out” and provided on a FFS basis. These include:

- Dental care;

- Specialty mental health services, such as targeted case management, partial hospitalization, and outpatient and inpatient mental health services. These are delivered through county mental health departments, which are responsible for intake, triage, and treatment for individuals meeting specific eligibility criteria for serious mental illness;

- Substance use disorder treatment services, delivered by local and county alcohol and drug programs;

- In-Home Supportive Services, which include personal assistance and other services enabling seniors and persons with disabilities to live safely at home. These are administered by counties, except in the seven MLTSS counties where these services are provided by the health plan;

- Home and community-based waiver services (HCBS), such as case management, continuing care nursing, day care, and respite services, for beneficiaries who meet the functional eligibility criteria for institutional care. Except in the seven MLTSS counties, where services authorized under the Multipurpose Senior Services HCBS waiver are covered by the health plan; and

- Skilled nursing facility services beyond 91 days, except in COHS counties and the seven MLTSS counties, where these services are provided by the health plan.

Provider Network Adequacy and Other Access Standards

Except for most COHS plans, Medi-Cal managed care plans are licensed by the California Department of Managed Health Care (DMHC) and are subject to statutory and regulatory consumer protections, including network adequacy requirements. Additionally, all DHCS contracts with health plans include specific network adequacy standards. COHS plans (except for the Health Plan of San Mateo) are exempt from statutory licensure requirements but must adhere to network adequacy requirements specified in their Medi-Cal contracts. (Appendix Table 1 details network adequacy standards in Medi-Cal managed care, and Appendix Table 2 describes standards for timely appointments.)

Recent Medi-Cal Managed Care Expansions

To prepare for the ACA coverage expansions in 2014, California applied for its “Bridge to Reform” Section 1115 demonstration waiver, which CMS approved in November 2010. This waiver enabled the state to implement the Low Income Health Program, expanding county-based coverage programs for low-income adults who would later become eligible for new ACA coverage options. The waiver also facilitated fundamental program changes aimed at enhancing health outcomes and ensuring the long-term financial stability of the Medi-Cal program. Mandatory enrollment of seniors and persons with disabilities (SPDs) in managed care was among these changes. Subsequent waiver amendments further extended managed care to additional populations and geographic areas. Overall, from 2011 to 2014, California transitioned or enrolled nearly 5 million Medi-Cal beneficiaries into managed care under the Bridge to Reform waiver. This included beneficiaries in rural counties, seniors and persons with disabilities, children previously covered by Healthy Families (the state’s CHIP program), individuals formerly in the Low-Income Health Program, and adults newly eligible for Medi-Cal under the ACA.

Seniors and Persons with Disabilities (SPDs)

Before 2011, mandatory managed care enrollment for seniors and persons with disabilities (SPDs) in California was limited to COHS counties. In other managed care models, SPD enrollment was voluntary. However, in 2011, following the approval of the Bridge to Reform waiver, the state began transitioning these beneficiaries—excluding those dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid—into managed care in 16 additional counties. These counties already had managed care for other Medi-Cal populations, but managed care for SPDs had previously been voluntary. Over 12 months starting in June 2011, nearly 240,000 SPDs were enrolled into managed care plans in these counties, with a choice of at least two plans. As California expanded mandatory managed care to rural counties in 2013, SPDs in these counties were also enrolled in plans. As of September 2014, 647,968 non-dually eligible seniors and persons with disabilities were enrolled in Medi-Cal managed care, representing 7.7% of total Medi-Cal managed care enrollment statewide.

Children Enrolled in the Healthy Families Program

Starting in 2013, children enrolled in the Healthy Families Program were moved into Medi-Cal. This shift aimed to simplify eligibility and coverage for children and families, improve children’s coverage through retroactive eligibility, enhance access to vaccines, expand mental health benefits, and eliminate premiums for lower-income children in the Healthy Families Program. The transition was also expected to generate budget savings for the state, as average rates paid to Medi-Cal plans were generally lower than those paid under the Healthy Families Program for a largely equivalent benefit package (adjusting for carve-outs). DHCS identified approximately 750,000 children eligible for transition to Medi-Cal, which was implemented in four phases to minimize service disruptions and ensure continuous access to care.

Adults in Low Income Health Program and Newly Eligible Adults under the ACA

Through the Low Income Health Program (LIHP), county and local entities enhanced their primary and specialty care delivery systems, implemented primary care medical homes, and enrolled over 630,000 uninsured adults aged 19-64 with incomes up to 200% of the federal poverty level. On January 1, 2014, all but 24,000 LIHP enrollees (whose incomes qualified them for subsidies for Marketplace plans) became eligible for Medi-Cal under the ACA Medicaid expansion and were enrolled in managed care plans.

Recently Added Services in Managed Care

Since 2011, California has expanded the benefits covered under managed care contracts through amendments to its Bridge to Reform waiver. These additions include adult day health services, mental health services, and, in seven demonstration counties, certain long-term services and supports.

Community-Based Adult Services (CBAS) Benefit

Before 2011, Adult Day Health Care (ADHC), a community-based day care program providing health, therapeutic, and social services for individuals at risk of nursing home placement, was an optional Medicaid State Plan service offered on a FFS basis. To achieve budget savings, Governor Brown’s January 2011 budget plan proposed eliminating the ADHC benefit. In March 2011, the state legislature voted to eliminate ADHC, pending CMS approval (which was delayed until April 2012). In August 2011, DHCS began transitioning ADHC participants from FFS to managed care plans, which were to coordinate their medical and social support needs. Subsequently, under a settlement with ADHC providers, the Community-Based Adult Services (CBAS) benefit was created to replace ADHC as a managed care benefit only. CBAS, accessible only to managed care enrollees, became the first community-based LTSS managed care plan benefit. Currently, CBAS providers serve 31,000 managed care enrollees statewide.

Managed Long-Term Services and Supports (MLTSS)

In January 2012, Governor Jerry Brown introduced his Coordinated Care Initiative (CCI), aimed at improving health outcomes and beneficiary satisfaction for low-income seniors and persons with disabilities, while achieving significant savings by rebalancing long-term services and supports towards home and community-based care. The state legislature enacted the CCI proposal in 2012 for implementation in seven counties in 2014. A key component of the CCI was a mandatory managed long-term services and supports (MLTSS) program. The CCI also included a demonstration program for persons dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid, which is discussed later.

In the seven CCI counties, Medi-Cal beneficiaries, including dually eligible enrollees previously exempt from managed care, are required to enroll in a managed care plan to receive their Medi-Cal benefits. This includes long-term services and supports such as consumer-directed In-Home Supportive Services, Community-Based Adult Services, the Multipurpose Services and Supports Program (the state’s HCBS waiver services for frail elders), and long-term (over 91 days) skilled nursing facility services. Other HCBS waiver services remain carved out. MLTSS coverage began on April 1, 2014. As of October 2015, over 300,000 dually eligible beneficiaries were enrolled in the MLTSS program in these seven counties.

Mental Health Services and Autism Care

In 2014, mental health services for mild to moderate mental illness were incorporated into managed care contracts, while specialty mental health services remained carved out. In 2015, behavioral health therapy for beneficiaries with autism or autism spectrum disorder was added as a Medi-Cal-covered benefit and was set to be covered by managed care plans in 2016.

Other Managed Care Initiatives

Dual Eligible Demonstration

As mentioned, the seven-county CCI also included a three-year Financial Alignment Demonstration (“Dual Demonstration”), authorized by the ACA to enhance coordinated healthcare delivery for individuals dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid. Under this demonstration, known as “Cal MediConnect,” dually eligible enrollees can choose to receive all their Medicare and Medicaid services—including medical, behavioral health, and institutional and home and community-based long-term services and supports—through a single managed care plan. Participation in the Dual Demonstration is limited to Medi-Cal plans already serving the area. Participating plans partner with other entities to provide some services, with the aim of delivering all care within a single, organized system. A Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) between the state and CMS outlines the Dual Demonstration’s principles and operational plan.

The Dual Demonstration places significant new demands on Medi-Cal health plans, including the responsibility to cover Medicare Part A, B, and D benefits, as well as Medi-Cal long-term services and supports. Plans must organize providers who may not have previously contracted with managed care plans or served Medicare beneficiaries. Under the Dual Demonstration, plans are also subject to detailed DHCS and CMS contract requirements to ensure continuity of care, conduct health risk assessments, and utilize person-centered, interdisciplinary care management teams. Enrollment in the Dual Demonstration is voluntary; as of December 1, 2015, 115,743 dually eligible enrollees—about a quarter of the eligible population—were enrolled.

Managed Care Data Initiatives and Dashboard

In late 2012, DHCS initiated the statewide Encounter Data Improvement Project (EDIP). EDIP’s goal is to improve the timeliness, accuracy, and completeness of encounter data reported by managed care plans. This is intended to enhance rate-setting and managed care monitoring, and to prepare for value-based purchasing. As part of this project, DHCS develops performance metrics and collaborates with managed care plans to address data collection and reporting deficiencies. This collaborative effort on data and metrics is crucial for performance reporting and will be foundational for value-based purchasing in the future.

To improve transparency regarding the quality of managed care plans, DHCS has created a Managed Care Performance Dashboard. This dashboard provides plan-reported data on various measures to help DHCS and stakeholders examine and understand managed care activity and performance at the state, model, and individual plan levels. The dashboard includes metrics related to enrollment, healthcare utilization, appeals and grievances, and quality of care, stratified by beneficiary population.

Key Challenges and Lessons

Access to Care

Provider payment rates and participation. Managed care plans are required to maintain adequate provider networks and capacity to ensure care access for their members. Historically, Medi-Cal FFS payment rates have been among the lowest Medicaid fees in the nation. Research indicates a positive correlation between fee levels and physician participation in Medicaid. In managed care, provider payment rates are contractually determined between plans and providers. However, persistently low rates continue to be a major factor in limiting provider participation and beneficiary access. California providers have sued the state arguing that Medi-Cal rates violate the “equal access” provision of federal Medicaid law. This provision mandates that payment rates be “consistent with economy and efficiency… and sufficient to enlist enough providers so that care and services are available under the plan at least to the extent that such care and services are available to the general population in the geographic area.” In November 2015, CMS issued a final rule implementing the equal access provision, requiring states to conduct regular access reviews and consider findings in setting provider rates. However, CMS limited this requirement to FFS rate-setting, noting that capitation payment rate standards are set in the June 2015 proposed rule on Medicaid managed care.

Data from a 2012 survey of Medi-Cal enrollees revealed that most beneficiaries found it easy to find a provider accepting Medi-Cal, but almost 1 in 5 experienced difficulty. Fewer than half of Medi-Cal enrollees reported it was easy to find a specialist or mental health provider accepting Medi-Cal; those in fair or poor health were more likely to report difficulty finding specialists. A separate analysis using national survey data found that Medi-Cal adults were significantly more likely than adults with Medicaid in other states to not have had a doctor visit (37% vs. 30%) or a specialist visit (48% vs. 36%), and to delay care due to appointment difficulties. Federally qualified health centers (FQHCs) and community clinics are crucial in providing primary care for Medi-Cal beneficiaries, but arranging specialist referrals remains a challenge.

A recent federal report shows that 54% of office-based physicians in California were accepting new Medicaid patients in 2013, compared to nearly 69% nationally. A 2013 California survey of physicians found a higher overall rate—62% accepting new Medi-Cal patients, compared to 75% for Medicare and 79% for privately insured patients. The rate was 70% among pediatricians, but just over 50% among other primary physicians. Facility-based specialists were most likely to accept new Medi-Cal patients, while only 36% of psychiatrists did so. In June 2015, the California State Auditor reported significant gaps in state oversight of Medi-Cal plan provider networks, a high volume of unanswered calls to the Medi-Cal managed care ombudsman, and inconsistent monitoring of Medi-Cal plans to ensure they meet beneficiaries’ medical needs.

Linguistic and cultural gaps in access. Another challenge in Medi-Cal is the linguistic and cultural disconnect between the provider workforce and California’s low-income population. A 2013 state analysis showed that 40% of Californians eligible for Medi-Cal reported a primary language other than English, with 13 languages meeting the state’s “Threshold Language” definition. Another study found that nearly 40% of all Californians and about 50% of Medi-Cal beneficiaries are Latino, yet only 5% of licensed physicians in California are Latino, and only 6% speak Spanish.

Rural areas. While urban areas generally have sufficient access to care, rural areas pose greater challenges for both publicly and privately insured patients. FQHCs, rural health centers (RHCs), and other health clinics are the backbone of ambulatory care in rural counties, playing an increasingly vital role in Medi-Cal managed care networks both in rural and urban areas.

Transitions to Managed Care

California’s transition of seniors and people with disabilities from FFS to managed care provided important lessons about the necessity of careful planning to ensure smooth transitions and prevent disruptions in care, especially for those with complex health needs.

Stakeholder engagement. Robust stakeholder engagement is essential for successful managed care transitions. DHCS increased engagement with beneficiaries, advocates, providers, and plans during the Healthy Families, Low Income Health Program transitions, and the Dual Demonstration. For example, in the Dual Demonstration, the state conducted extensive webinars, workshops, and stakeholder meetings, which state officials credited with improving outreach effectiveness. DHCS also created a dedicated webpage to report on meetings, updates, and notices.

Data issues. In the SPD transition, inaccurate enrollee contact information, privacy rules limiting plan and provider access to beneficiary medical records, and other data issues hindered timely care coordination. The state improved data-sharing processes in the Dual Demonstration, giving plans more time to contact enrollees and prepare for their needs. However, contacting beneficiaries to complete health assessments, particularly for newly eligible individuals and those without stable addresses, remains challenging.

Continuity-of-care protections. SPDs were allowed to request continued access to an out-of-network provider for 12 months post-enrollment. However, a lack of understanding of this provision among plans, providers, and beneficiaries led to unnecessary disruptions in patient-provider relationships. In subsequent transitions, DHCS and plans increased communication with enrollees and providers to improve understanding of continuity-of-care protections. DHCS also incorporated specific continuity-of-care requirements into managed care contracts.

Enrollment processes. Leading up to the Dual Demonstration, advocates and plans advocated for greater transparency in the enrollment process and beneficiary protections, including the right to opt out or disenroll. In response, the state published the enrollment schedule and mailing dates for beneficiary notices to aid outreach and education efforts. The state also addressed issues arising in the beneficiary notice/enrollment process. Advocates and plans worked with DHCS to improve the managed care enrollment process for beneficiaries with LTSS needs and dually eligible beneficiaries.

Coordination with carve-out services. Coordination between plan and carve-out services is an ongoing challenge. This was evident in the SPD transition, especially regarding mental health care, where prescription drugs were provided by plans, while specialty mental health services were carved out and provided by county mental health departments. In the MLTSS transition, coordination with remaining carved-out waiver services was also problematic. Discrepancies between waiver service care managers and health plans in assessing beneficiary needs and care goals can create access barriers.

Improving Quality

Performance measurement and monitoring. Managed care contracting enables states to measure and enforce accountability for quality. California requires Medi-Cal managed care plans to regularly submit quality-related reports, including CAHPS survey findings, HEDIS scores, member complaint reports, and other statistical reports.

Transparency. DHCS’s collection and monitoring of quality data, and the public availability of plan performance data on the Managed Care Performance Dashboard, enhance state oversight, plan quality transparency, and value-based purchasing strategies. DHCS collaborates with Medi-Cal plans to refine quality measures and enforcement mechanisms, including developing corrective action plans for quality reporting and outcomes. DHCS also hosts an annual quality forum to recognize plans for quality performance progress. Underperforming plans may face enforcement actions, corrective action plans, or disadvantages in the state’s auto-assignment algorithm.

Special reports for Dual Demonstration plans. Plans in the Dual Demonstration must submit additional reports to CMS, including quality metrics for both Medi-Cal and Medicare services. DHCS and CMS review these reports and work with plans to ensure consistent data reporting for evaluation. DHCS recently published the first quarterly Health Risk Assessment Dashboard, comparing plans’ compliance with Health Risk Assessment requirements for Dual Demonstration members.

Major Current Issues

Medicaid Managed Care Rule

CMS’s proposed rule on Medicaid managed care aims to modernize and fundamentally reshape the regulatory framework for managed care. It seeks to strengthen beneficiary protections and network adequacy requirements, enhance fiscal integrity of capitation rates, address healthcare delivery and payment reform, increase state and plan accountability for access and quality, and strengthen oversight of Medicaid managed care programs. If these provisions are maintained in the final rule, expected in Spring 2016, they could significantly impact provider networks, beneficiary access, provider payment, and other aspects of the Medi-Cal managed care program.

In a public comment letter to CMS, the California Hospital Association generally supported the rule’s direction but raised concerns, particularly about proposed limitations on states’ ability to direct plan expenditures and payments to specific providers. They argued this could interfere with supplemental payments to safety-net and public hospitals serving large Medicaid populations. The letter also addressed other provisions, recommending stronger standards in some areas and more flexibility in others, and emphasizing the need for adequate state resources to audit and enforce regulatory standards.

Section 1115 Waiver Renewal

California’s Bridge to Reform demonstration waiver expired on October 31, 2015. DHCS applied for a five-year extension, named “Medi-Cal 2020,” with terms announced on December 30, 2015. A key component of this waiver is the Public Hospital Redesign and Incentives in Medi-Cal (PRIME) fund, a nearly $7.5 billion pool for delivery system reform in California’s public hospital systems over five years. PRIME builds on the Delivery System Reform Incentive Program (DSRIP) from the original waiver. DHCS will use PRIME to fund public provider system projects aimed at transforming care delivery and enhancing these systems’ ability to be paid under risk-based alternative payment models (APMs). The waiver documents indicate that CMS and the state will assess PRIME’s success partly by measuring progress in adopting APMs through Medi-Cal managed care. The exact interaction between DSRIP and PRIME pools with the Medi-Cal managed care program, and the implications for plans and members, remain to be seen.

Medi-Cal 2020’s “Whole Person Care Pilots,” designed to provide more integrated care for vulnerable, high-utilizing beneficiaries, also involve Medi-Cal plans. These county-based pilots encourage innovative partnerships between Medi-Cal managed care plans, safety-net providers, community-based service providers, and affordable housing providers. These partnerships aim to address social determinants of health, integrate physical and behavioral healthcare, and improve beneficiary health and well-being.

Looking Ahead

Between 2011 and 2015, California significantly expanded its managed care program, extending it to 28 rural counties, transitioning or enrolling almost 5 million beneficiaries, incorporating adult day health and mental health services, and launching MLTSS and Dual Demonstration programs in seven counties. Today, Medi-Cal managed care plans operate in all 58 California counties, covering over three-quarters of Medi-Cal enrollees. To accommodate this growth, plans have been challenged to rapidly expand provider networks and operations to meet increased service demand, call center volume, utilization management, care management, quality improvement, and claims processing. The state has also faced challenges in providing adequate notice and education to enrollees transitioning to managed care and ensuring timely data provision to health plans.

Other states considering managed care expansions, especially for populations with complex care needs, can learn from California’s experience. Managed care may not resolve long-standing access issues caused by provider shortages, low Medicaid payment rates, and limited provider participation. As states expand managed care to more beneficiaries, ensuring adequate plan networks could become more challenging. Robust transition planning is crucial to minimize care disruptions when mandating managed care enrollment for new FFS beneficiary groups. Engaging beneficiaries, providers, advocates, and other stakeholders in planning and implementation is essential to ensure beneficiaries can navigate their plans and are informed about their rights and options. Data-sharing systems and information systems are vital for supporting managed care transitions and ongoing monitoring, oversight, and performance improvement, which are integral to plan and state accountability.

California, like many states, is increasingly focused on improving managed care contractor performance. Key focus areas include delivery system transformation for better care at lower costs, enhanced care integration, expansion of managed long-term services and supports, transparency in health outcomes, and improved population health. To meet these challenges, managed care plans must develop new engagement strategies for beneficiaries, partner with community-based social services and housing organizations, and structure provider payment models to promote quality and outcomes, all within funding constraints. Finally, as managed care evolves, close state monitoring and rigorous enforcement of federal and state requirements will remain crucial to optimize its potential for coordinated care and minimize access gaps.

The authors wish to acknowledge valuable input and assistance from Michael Engelhard, Donna Laverdiere, and Lisa Shugarman, all of Health Management Associates.

Executive Summary

Appendix